Olli Wisdom: Rest In Space

Everyone who is part of the Goa/Psychedelic Trance scene has clear memories of their first experiences with this unique brand of music. Mine are inextricably linked with Olli Wisdom of Space Tribe, whose passing on August 23, 2021 is a massive loss to all of us in the scene. What follows is a detailed tribute outlining the formative experience hearing Olli for the first time and how he went from being an idol to a friend over a long arc of 27 years.

It’s hard to put into words the multidimensional qualities and impact of such a cosmic being, and his artistic legacy is intertwined with who he was personally and with our shared experiences, much like Space Tribe was not just about the music but the visual element as well as the concept and energetic framework. SO – there will be a lot of words here in an attempt to paint a portrait worthy of a figure who had such an impact on this global (and dare I say intergalactic) movement, with a lot of personal backstory that leads into an overview of his legacy.

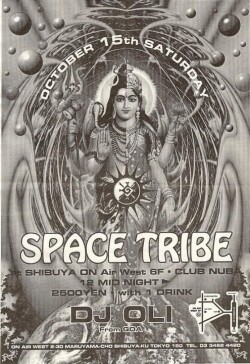

On October 15, 1994, a friend took me to a club in Tokyo and the experience I had there completely shifted the direction of my life. As I walked onto the dance floor, it seemed as if I had crossed the threshold into a parallel dimension and was transported to a nightclub on another planet. Ultraviolet lighting illuminated geometric artwork while music that was completely alien to our earthly plane came through the sound system.

On October 15, 1994, a friend took me to a club in Tokyo and the experience I had there completely shifted the direction of my life. As I walked onto the dance floor, it seemed as if I had crossed the threshold into a parallel dimension and was transported to a nightclub on another planet. Ultraviolet lighting illuminated geometric artwork while music that was completely alien to our earthly plane came through the sound system.

One wall hanging in particular caught my eye: fractals surrounding the Japanese characters for the word Genki, the Japanese word for the innate vitality and vibrancy that can be seen as ‘health’ but its root meaning refers to ‘original energy’ or ‘source energy’.

Dancing more and more to this music that was a new but somehow familiar language to me, I started to relate to the sounds I was listening to in a particular way. Everything that I was hearing was completely otherworldly, lots of whooshes and zaps, sounds that couldn’t be identified by a physical instrument in the way that we can recognize the connection between the form and sound of a piano, flute, or violin. As I listened and moved through the venue, a number of thoughts simultaneously came to mind: that I was hearing the sounds of outer space… that I was listening to what it was like to be inside a computer … that if mathematical equations were translated into sound, they would sound like this … that this might be what aliens would hear if they had venues on their planets where they gathered to move their bodies to invisible vibrations that were being communicated through ‘sound’ or some other medium.

Being trained and active at the time in the classical music world (and I still am), some other thoughts came to me: that the entire history of classical music had tried to communicate something beyond this plane, composers working to the best of their abilities with the instruments at their disposal, and they were all heading in the direction of what I was listening to. Berlioz had dreamed of a 400-person orchestra, and now there was this amplified sound that could produce the power and depth he’d imagined. Hindemith spoke of ‘Gebrauchtsmusik’ – ‘usable music’ – and here we were not just sitting and appreciating it passively in a concert hall but moving to it in dynamic response to it. Wagner’s concept of Gesamstskunstwerk – a total work of art – was put into practice in a setting adorned with colourful shapes and patterns that looked like the music as the lighting effects were coordinated with the sonic patterns.

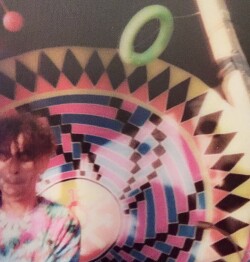

The flyer for the event stated that DJ Oli was ‘from Goa’, and one of my friends prior to the event had stated that this meant it was some good music. I have no recollection of even having seen Olli (as he would spell his name most regularly – there were at least three spellings floating around) as there was another guy there bouncing around and working the lights, and I thought he was the person behind the whole thing (I really had no idea how the whole ‘show’ worked). But some time later at the shop Connected, I saw photos of the event (none of which I have) that included a photo of Olli grinning with his eyes closed and I was told that he was the DJ.

The flyer for the event stated that DJ Oli was ‘from Goa’, and one of my friends prior to the event had stated that this meant it was some good music. I have no recollection of even having seen Olli (as he would spell his name most regularly – there were at least three spellings floating around) as there was another guy there bouncing around and working the lights, and I thought he was the person behind the whole thing (I really had no idea how the whole ‘show’ worked). But some time later at the shop Connected, I saw photos of the event (none of which I have) that included a photo of Olli grinning with his eyes closed and I was told that he was the DJ.

At this event I met David Dobson, who had not only arranged the party but was also importing and selling the colourful Space Tribe clothing that I saw people there wearing: leggings and shirts with vibrant colours that glowed in the black light, geometrical patterns, and what looked like stickers on the arms and legs of these items, all of which created a sense of colour therapy as people moved about in the UV-illuminated space. By the time I realized that these had been available at the event, they had sold everything, so it was only the following February that David got a new shipment and I got my first of many outfits from the brand.

When I was 10 years old I had an incredibly vivid dream that I never forgot in which I felt myself as a much larger being than I experienced in my daily life, and at one point in the long dream (which ended on a pyramid that years later I would identify as being at Teotihuacán), I was rollerskating around a modern neon-lit night-time city; with me were my sister and some of her friends, and we ended up at a club with strange futuristic music playing. Well … my sister and all of those friends were in fact living in Tokyo at the time that I first had heard Olli play, and I would end up introducing them all to this scene and all that went with it; that dream was in fact not just a sign but an audible and visual premonition of what was coming my way, of a key bookmark in my life.

Olli and the Space Tribe clothing and music (I’d heard a couple of his tracks by this point) would come to represent that magical introduction I’d had to this other world, as did the name Space Tribe and the concept it suggested: a kind of secret society of space travellers gathering together to reconnect to their source nature (‘genki’) before going back out into the world. While there were some great events happening in Tokyo at the time (I was a regular at the amazing Odyssey parties), there was something unique and pivotal about that particular experience, a particular quality to the energy of the setting and event, to how Olli held the whole thing. I just knew that this was something different, that it woke up something within me, and that I wanted ‘in’ to whatever this was.

As I started buying releases of Goa music, Olli’s productions stood out too, the mainstay of the time being Machine Elf, which was included in the mixtapes given to me by two local Tokyo DJs (Jay and Mayuri) in late 1994 – still one of the all-time great tracks of the genre and one that immediately sends me back to that magical time:

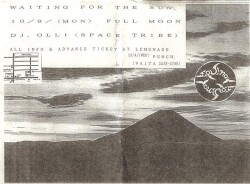

There were rumours that Olli was going to play an outdoor party that I would attend in the summer of 1995 (my first outdoor event) but in fact he wasn’t booked. When I went to an open-air Autumn Equinox party held by the Equinox party crew in September 1995, they were handing out flyers to a Full Moon Party at which Olli would be playing a few weeks later, October 9, 1995. (The black-and-white photocopied flyer couldn’t be in starker contrast to the colour of the clothing he produced.) Of course I bought a ticket and went along with some close friends, and to say that it was another transformative experience would be to completely understate the case.

There were rumours that Olli was going to play an outdoor party that I would attend in the summer of 1995 (my first outdoor event) but in fact he wasn’t booked. When I went to an open-air Autumn Equinox party held by the Equinox party crew in September 1995, they were handing out flyers to a Full Moon Party at which Olli would be playing a few weeks later, October 9, 1995. (The black-and-white photocopied flyer couldn’t be in starker contrast to the colour of the clothing he produced.) Of course I bought a ticket and went along with some close friends, and to say that it was another transformative experience would be to completely understate the case.

The full moon illuminated the outdoor field in which we were located, as well as the side of Mount Fuji. Before the music started I introduced myself to Olli very briefly – still being starstruck – and that night had the most amazing experience through that 10-hour event that he played entirely on his own. I was impressed by Olli coming out of the DJ booth (or rather DJ teepee) to dance at various times (something I’ve since adopted in my own sets and which seems to generate a lot of attention). At dawn, a flock of 100 birds circled the snowy peak of Fuji and then the sun broke from behind it … and the music matched fully what we all experienced, and a field of 500 dancers stood there with tears in their eyes looking at a sight that one would normally miss by virtue of being asleep (something symbolic there for sure).

The full moon illuminated the outdoor field in which we were located, as well as the side of Mount Fuji. Before the music started I introduced myself to Olli very briefly – still being starstruck – and that night had the most amazing experience through that 10-hour event that he played entirely on his own. I was impressed by Olli coming out of the DJ booth (or rather DJ teepee) to dance at various times (something I’ve since adopted in my own sets and which seems to generate a lot of attention). At dawn, a flock of 100 birds circled the snowy peak of Fuji and then the sun broke from behind it … and the music matched fully what we all experienced, and a field of 500 dancers stood there with tears in their eyes looking at a sight that one would normally miss by virtue of being asleep (something symbolic there for sure).

And when a track suddenly stopped and the words ‘YOU – are the alien!’ came through the speakers, he was pointing at me. I got the message.

And when a track suddenly stopped and the words ‘YOU – are the alien!’ came through the speakers, he was pointing at me. I got the message.

These experiences and the other parties I attended had impacted me so much that I moved to London to get closer to what I thought was the heart of the scene, meeting a number of its key players. But Olli lived in Australia, a long way away. One day in late 1996 or early 1997, I visited Mark Neal, who designed the bulk of the artwork for the releases of the music in the scene; he had just come back from Australia, where he had spent some time staying with Olli. He had a demo cassette of the first solo Space Tribe album on Spirit Zone, Sonic Mandala, which he put on while we spoke, and he mentioned having discussed with Olli the various kinds of music in the Goa genre, highlighting the clarity with which the intrepid musician had described the different flavours of music and what worked at what time for what reason. He said he’d never heard anyone so clearly articulate the breadth of the music in words, as well as its impact – this was the kind of overarching cohesiveness that I’d experienced the two times I’d heard him.

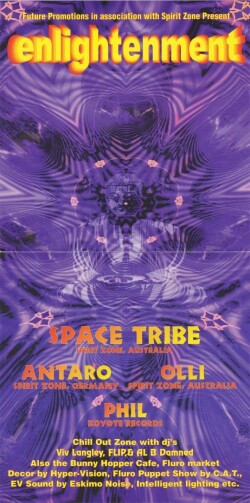

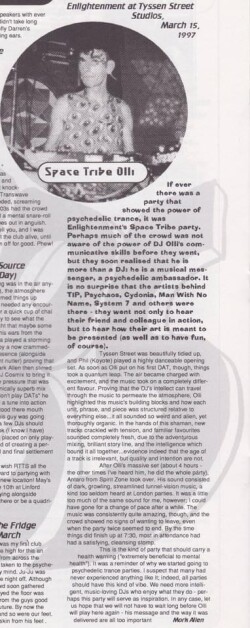

Within a couple of months, Olli was playing in London, a March 15, 1997 Enlightenment party at the dismal regular party venue Tyssen Street. I had gotten intel that he had recently broken up with his wife and had a case of double pneumonia, but fortunately he recovered and could play. Mark re-introduced me to Olli before his set started and he greeted me warmly; he had eye makeup on and was of course fluoro’d up.

Within a couple of months, Olli was playing in London, a March 15, 1997 Enlightenment party at the dismal regular party venue Tyssen Street. I had gotten intel that he had recently broken up with his wife and had a case of double pneumonia, but fortunately he recovered and could play. Mark re-introduced me to Olli before his set started and he greeted me warmly; he had eye makeup on and was of course fluoro’d up.

Even before he even started to play something remarkable happened: he walked on stage behind the DJ who was playing and it was like I could hear a crackling of excitement in the air, as though there was inaudible applause that was somehow tangible… it was as if the ceiling was starting to rise and the energetic parameters of the event were broadening. The second he put on the first track, the entire place exploded, like the ceiling and walls had totally been blown open. Mayhem ensued.

London was in my experience a pretty snooty crowd, even in this underground scene – quite different from my first year and a half of attending events in Japan – and the folks at this event were divided into those who totally went wild to what was happening and others who stood back not quite getting the broad-spectrum storyline of Olli’s set construction and the fact that he dropped a few classic tunes when they wanted to hear only things they didn’t know.

London was in my experience a pretty snooty crowd, even in this underground scene – quite different from my first year and a half of attending events in Japan – and the folks at this event were divided into those who totally went wild to what was happening and others who stood back not quite getting the broad-spectrum storyline of Olli’s set construction and the fact that he dropped a few classic tunes when they wanted to hear only things they didn’t know.

One moment when I could recognize the power of what was going on was when a French friend of mine who always wanted the newest music was completely losing it as Olli played the Slinky Nuns belter, ‘Shitty Stick (Better Than A Poke In The Eye With)’; the track was a year old but this ‘new tunes only’ guy was going ballistic… and when I went up beside him and said, ‘Well?’ he just looked at me and shook his head, speechless. Olli played for four hours – the shortest he would play at the time – and it was epic to say the least. I wrote a rave review for Dream Creation magazine, and my using the moniker Mork Alien led a lot of people to think it was Mark Allen (whom I knew and who called me up asking if I could use another name).

One moment when I could recognize the power of what was going on was when a French friend of mine who always wanted the newest music was completely losing it as Olli played the Slinky Nuns belter, ‘Shitty Stick (Better Than A Poke In The Eye With)’; the track was a year old but this ‘new tunes only’ guy was going ballistic… and when I went up beside him and said, ‘Well?’ he just looked at me and shook his head, speechless. Olli played for four hours – the shortest he would play at the time – and it was epic to say the least. I wrote a rave review for Dream Creation magazine, and my using the moniker Mork Alien led a lot of people to think it was Mark Allen (whom I knew and who called me up asking if I could use another name).

After the event, Mark Neal offered me a lift home together with Olli. I was still somewhat pixelated from the experience and still rather starstruck, despite Olli’s affable nature. When we got to Mark’s car, we found that the passenger side window had been shattered. We swept the shards off the passenger seat, Mark quite naturally feeling glum, and Olli got in the back while I sat by the open window – a breath of fresh air, quite literally. A minute into the drive, Olli pipes up, ‘Hey Mark, could you shut the window? It’s a bit cold back here!’ Mark almost started sobbing, I had to hold back a laugh, and Olli said, ‘You’re going to laugh about it eventually, so you might as well laugh now.’ I never forgot that – truly words to live by (and I’m sure he did).

I knew Olli would be playing in San Francisco that August, along with Simon Posford and Tsuyoshi, both of whom had invited me to tag along, but it was unfortunately out of the question. But circumstances did align for me to go to Solipse in Hungary in 1999, as I left Japan from my second stint living there and prepared to move back to Canada. I had in the meantime started DJing in Japan, and my experiences hearing Olli were formative in how it is that I approached set construction. Despite having heard him only three times up until then (and only having general impressions of the first), I remembered various elements of how he put stories together, how there were chapters, sometimes matching transitions while at other times there were clean breaks and full starts signalling a new beginning as a page was turned. All of this flew in the face of the standard approach to mixing, where DJs opted for smooth blends and uniformity as opposed to a full range of musical languages presented in a creative blend.

At Solipse, Olli was playing a 4-hour morning set that was my main priority to attend. I’d been sick the day before, unable to go to the site (this was a few days in), but I was there bright and early for when he showed up in his silver one-piece suit. I remember he started with X-Dream’s Coming Soon and once again, there was mayhem throughout the four hours. I remember this one track that completely blew my mind, with an incredibly upbeat atmosphere, playful electronic sounds, and a great sample, ‘Man… that is soooo deeep.’ When I asked what it was, he said it was one of his new ones – and it has indeed become a classic.

Moving back to Canada in the autumn of 1999 was somewhat like being in the desert, parched for an injection of the kind of cosmic vibes I’d experienced in five years of events in Europe and Japan. I heard through the grapevine that Olli was due to play in Seattle around 2001 and somehow arranged, in the early days before Facebook, to book a bus down and stay with someone local. As soon as I arrived in the city, I found out that the location had fallen through and Olli had flown off to San Francisco – a real bummer, not just because I had made the trip but since this fellow I’d connected with had some alternative venues he might have been able to help with.

Finally in 2004, Olli came to Vancouver for the first time at local promoter Goa Pete’s first Karma event, held outdoors about an hour out of the city. Hearing him again was like a breath of fresh air. Although his music was continuing to evolve in style, there was that palpable familiar quality of energy to the experience: it was like there was a massive wall behind him, with a high ceiling and depth beneath the ground, and that was the energetic room in which the event took place. Even as the music changed and as each event had its own flavour, the energetic signature of each event had some of the same qualities: a psychedelic ‘anything goes’ flavour in the space, like a cosmic celebratory carnival with a no-nonsense quality of certainty that was very distinctive.

Finally in 2004, Olli came to Vancouver for the first time at local promoter Goa Pete’s first Karma event, held outdoors about an hour out of the city. Hearing him again was like a breath of fresh air. Although his music was continuing to evolve in style, there was that palpable familiar quality of energy to the experience: it was like there was a massive wall behind him, with a high ceiling and depth beneath the ground, and that was the energetic room in which the event took place. Even as the music changed and as each event had its own flavour, the energetic signature of each event had some of the same qualities: a psychedelic ‘anything goes’ flavour in the space, like a cosmic celebratory carnival with a no-nonsense quality of certainty that was very distinctive.

He would have another half-dozen gigs in the Vancouver area over the next 15 years or so, including a memorable outdoor party in which he headlined with Domino in 2009, and on my trips to London he would invite me to drop in to say hello. One visit late in 2012 was a particularly meaningful one. While I was spending some time with Dick Trevor at the Eclipse Festival in Montreal that summer, Olli called up Dick and told him that he could give me the news of his cancer diagnosis, which he wanted to keep under wraps from the general public to avoid an onslaught of sympathy and energetic attention. When I went to London in December of that year, he invited me for a visit despite the fact that he was weakened from his treatment.

He would have another half-dozen gigs in the Vancouver area over the next 15 years or so, including a memorable outdoor party in which he headlined with Domino in 2009, and on my trips to London he would invite me to drop in to say hello. One visit late in 2012 was a particularly meaningful one. While I was spending some time with Dick Trevor at the Eclipse Festival in Montreal that summer, Olli called up Dick and told him that he could give me the news of his cancer diagnosis, which he wanted to keep under wraps from the general public to avoid an onslaught of sympathy and energetic attention. When I went to London in December of that year, he invited me for a visit despite the fact that he was weakened from his treatment.

Seeing this powerhouse who’d always seemed larger than life on a mattress in his living room, his trademark mop of hair thinned due to medical interventions, was a bit of a shock but he was completely nonplussed and still totally himself. He was fascinated by the science of the treatment he was getting, and was extremely philosophical about his situation, saying he’d never even expected he’d have lived that long and so it was all a bonus. I made us tea and we just chatted about a variety of things, and he gave me a few encouraging words that offered me a perspective shift about the state of the party scene in my hometown.

He made quite an amazing recovery and all of our subsequent visits to each others’ cities found us spending more time together, talking about both the mundane and the musical. On his last few visits to Vancouver, I ended up helping Goa Pete by driving Olli to and from the gigs and the airport, which I was more than happy to do. On one dismally rainy day before his flight home, we drove around Stanley Park and witnessed some runners in some kind of race and he delighted in pointing out how miserable all these diligent athletes appeared to be.

He made quite an amazing recovery and all of our subsequent visits to each others’ cities found us spending more time together, talking about both the mundane and the musical. On his last few visits to Vancouver, I ended up helping Goa Pete by driving Olli to and from the gigs and the airport, which I was more than happy to do. On one dismally rainy day before his flight home, we drove around Stanley Park and witnessed some runners in some kind of race and he delighted in pointing out how miserable all these diligent athletes appeared to be.

His powers of observation and ability to articulate the truth were astounding. On one of his visits to Vancouver, immigration pulled him over at the airport and found out by going through his emails that he was coming to play a gig when he didn’t have an artist’s visa. He was held for about four hours, and when one of the officials said to him, ‘You’re taking business away from locals’, his retort was razor-sharp. ‘Actually, I’m generating lots of money for the local economy: because I have an international reputation, tickets have been sold which creates income for the club, the bartenders, the staff, the sound technicians, the local organizer… a lot of local revenue is being created by my being here.’ Silence. ‘Well, you still shouldn’t be here.’ And then they let him in and he played the gig.

For all my interest in the roots of the scene and reputation of being a ‘Goa Guardian’ of its musical past, I still very much understand Olli’s perspective that the past is the past and the scene is in the present looking towards the future (I mean, he did produce a track and album entitled ‘The Future’s Right Now’). It was never about the past, and he wasn’t a fan of the retro concept as he said he thought it was going back to create something in the present that is no longer new. He noted that back at the time, one would play the newest tracks from that season, so in 94 you would play tracks from that year, in 95 those ones, in 96 those ones… not a full range of tracks from the 90s, as is done in retro sets now. And – he also acknowledged paradoxically (there’s always a paradox) that there was the reality of ‘the right track at the right time’, as when I pointed out his playing of Shitty Stick and Mr. Redeemer at Tyssen Street – these were the exceptions that proved the rule.

His own attitudes towards music and the framework in which it was presented evolved too, a natural process as the scene shifted over the years. In his early years of performing he preferred to play the full night so that he could craft the whole story from beginning to end as a shamanic journey. I know from how I heard others speak of this at the time that this was sometimes considered a sign of egotism, when it was clear to me and others who experienced his storytelling and mastery that it was actually his sourced intention to craft a cohesive journey for the whole event; as someone who had danced through countless parties himself, he was very well acquainted with what worked well at what time for the people on the dance floor (as per Mark Neal’s statements above). He was able to do this in the early years in both Japan and Bali, with some amazing results: David told me of a stormy night at an early party in Japan where Olli just powered through and the dancers did the same, and the inclement weather transformed to make way for a truly ecstatic sunrise. But as the scene grew, he moved towards four-hour sets so that he could still have time to play with enough variety but also be included in a more traditional multi-DJ line-up.

His own attitudes towards music and the framework in which it was presented evolved too, a natural process as the scene shifted over the years. In his early years of performing he preferred to play the full night so that he could craft the whole story from beginning to end as a shamanic journey. I know from how I heard others speak of this at the time that this was sometimes considered a sign of egotism, when it was clear to me and others who experienced his storytelling and mastery that it was actually his sourced intention to craft a cohesive journey for the whole event; as someone who had danced through countless parties himself, he was very well acquainted with what worked well at what time for the people on the dance floor (as per Mark Neal’s statements above). He was able to do this in the early years in both Japan and Bali, with some amazing results: David told me of a stormy night at an early party in Japan where Olli just powered through and the dancers did the same, and the inclement weather transformed to make way for a truly ecstatic sunrise. But as the scene grew, he moved towards four-hour sets so that he could still have time to play with enough variety but also be included in a more traditional multi-DJ line-up.

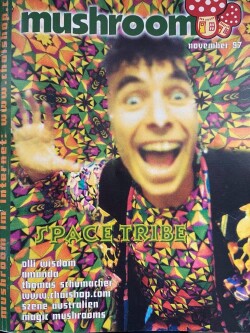

In a Mushroom Magazine interview in 1997, he stated that he thought that live shows were not aligned with this scene, but as he produced more and more music, that perspective also shifted and he began to deliver sets of just his own music. And he would then move from solo productions to working exclusively with others, enjoying the camaraderie and creative inspiration of being with others in the studio rather than ‘at work’ alone, and he created tracks with a wide range of other producers in the scene.

In the last decade, his main focus was on his Mad Tribe project with Mad Maxx, who like me had been a great fan of Olli’s DJ sets and then became his primary musical partner and closest friend. The retro-futuristic flavour of Mad Tribe productions, with spoken samples from 1950s sci-fi flicks, was one that seemed a natural continuation of his alternate view of the future seen through the past from the present. He delighted as much in the creation of the music as he did in the development of the artwork with his brother Miki (who runs Space Tribe clothing) and in performing at gigs.

In the last decade, his main focus was on his Mad Tribe project with Mad Maxx, who like me had been a great fan of Olli’s DJ sets and then became his primary musical partner and closest friend. The retro-futuristic flavour of Mad Tribe productions, with spoken samples from 1950s sci-fi flicks, was one that seemed a natural continuation of his alternate view of the future seen through the past from the present. He delighted as much in the creation of the music as he did in the development of the artwork with his brother Miki (who runs Space Tribe clothing) and in performing at gigs.

While he went with the flow of the evolution of the scene, he also had very real concerns about its well-being. I’ll never forget the look of shock on his face when, backstage at a Solstice event in Tokyo a few years ago, a fight erupted in the crowd; anything like this had been unheard of in Japan but had started to happen recently, and was the total antithesis of what he and the scene stand for. He was aware of and concerned about various power-seeking and undermining business approaches that existed behind the scenes, and he was uncompromising in sticking to his approach. He spoke of ‘our beautiful scene’ and always held what it was and had the power to be.

And no wonder he did: Olli may have had more influence on more key elements of this global movement than any one other person. That Gesamstkunstwerk total-art-concept combination of multi-sensory boundary-breaking events did make it a beautiful scene, where sound and colour expanded beyond normal parameters (UV light helping us see beyond the normal visible spectrum was a way to open the doors to our consciousness doing the same thing) to create a truly expansive celebration of being alive on this planet at this time while sustaining a connection to all other times and planets and beyond. No one else worked with producing music, performing his own and others’, and crafting the concept of the setting like he did, with a visual framework of full-spectrum colour that, as David put it to me at the time, was like colour therapy as those present moved through the space in their vibrant clothing.

But beyond that it was the ENERGY that he brought, the gateways that he opened – that’s what it was all about. As much as there was his individual flavour in everything he did, it actually wasn’t about him but rather the massive portal that he opened for everyone present by virtue of his fierce commitment and deep belief in what he was doing. His non-negotiable ‘this is IT’ infused everything he did and when he was behind the decks as a DJ, it was like a force of nature had been unleashed: it wasn’t even about what was coming through the speakers and what was happening on the dance floor, it was about what this all represented, where it was coming from – beyond our perceptions – and where it was going (and us along with it).

Every set stood on its own, with its own individual character, like a living being that was conceived, gestated, and birthed, but the universality of each experience was also there: the unfolding of the present moment, the realization that we are all one expression of Oneness located somewhere in Space (wherever that is), that Now is all we have, and that we are awake to this and going to celebrate it out loud. For all the emotional flavours in the music he played (in the 90s he used coloured highlighters to indicate on DAT labels some of the different emotional categories of tracks), there was always a journey and magical experience of a cosmic circus. As existential as this all was, it was also about having FUN – something that has unfortunately somewhat faded from the scene, along with much of the colour that he brought to it and embodied.

Over the last years, in each moment I spent with him he seemed to embody the same curiosity and engagement, whether it was driving through the park laughing at soaking joggers, meeting up at the airport at Heathrow while we were off to separate gigs, driving in London in his new Paceman car (naturally, we thought he should affix an S in front of it so it really represented this Spaceman), or listening to some new tunes.

And yet the more we got to see each other, the less we needed to say – there was just the understanding of who we were, what we’d experienced in the 90s and since, and the simplicity of being in the moment discussing whatever was on the table. On his last visit to Vancouver with Max, we made a pitstop at my place and as he got Miki on Skype to discuss some artwork in development, I pulled out some of the old Space Tribe outfits from my collection. Olli couldn’t believe how some of the pieces were still in mint condition, really looking fresh – “and I KNOW you partied hard and wore them lots!”

And yet the more we got to see each other, the less we needed to say – there was just the understanding of who we were, what we’d experienced in the 90s and since, and the simplicity of being in the moment discussing whatever was on the table. On his last visit to Vancouver with Max, we made a pitstop at my place and as he got Miki on Skype to discuss some artwork in development, I pulled out some of the old Space Tribe outfits from my collection. Olli couldn’t believe how some of the pieces were still in mint condition, really looking fresh – “and I KNOW you partied hard and wore them lots!”

As we were packing up to leave, I for the first time got a close-up view of the tattoo on his shoulder and saw that it was of a jester, so I asked about it; he spoke to the joker who saw all, the cosmic trickster, and other archetypal elements of the symbol. Back in the 90s I’d had a fluoro jester’s cap as the same archetype had resonated with me, and chose my DJ name based on the book The Solitaire Mystery, which centres around a jester who sees through the delusion and who makes a story out of sentences provided by the other cards in the deck. The fact that the shoulder of the DJ of my dreams (literally) had the symbol that I had unwittingly been drawn to, down to the moniker I chose, speaks to that deeper web of connectivity that he made available in all of his performances – we might not know at the time or even later find out, but there was some deeper fabric binding us together that was awoken during those events and in this magical scene that he helped create.

Our last video call took place in early 2020, not long before the lockdowns, when he called up asking for a few of his early tracks that he couldn’t locate for a retro set in Israel – he chuckled at his not having them himself but knowing who would. The party didn’t end up happening and we had just a couple of brief texts after that. I’m glad that I had said everything to him that I most deeply wanted to. I had once articulated to him my observation that while a lot of producers and performers dipped their toes in the water or went for swims in the lifestyle, he lived it 24/7, 365 days a year, boots on the ground in Goa and Bali (and Koh Phangan before that), fully living the life and never leaving it. I believe that this ground-level immersion and experience as an intrepid psychonaut informed whatever he did with a depth of grounding and fierceness of authenticity that was unparalleled. His commitment was bone-deep and I believe this is why anyone hearing him perform felt it so deeply.

His sudden departure on a Full Moon – a Blue Moon, no less – leaves a massive black hole in a scene that he was so influential in bringing to life. It’s impossible to count how many people over the last 30+ years his presence touched directly through his performances, in addition to indirectly through his music and clothing. He was a visionary shaman who knew what was his to do and who did it with no regrets. While we mourn his departure, we can be grateful for what was provided and made possible in the hands of this shaman, and strive to live as he encouraged us through his music and work: to remember that ‘we are all connected in the great circle of life’ and that ‘we are star travellers.’ And as he and we ‘journey into the next world’ in our ‘waking dreams’, to ‘live what you love every moment of your life, right now’ – as he did. You’re going to laugh about it one of these days, so you might as well laugh now.

His sudden departure on a Full Moon – a Blue Moon, no less – leaves a massive black hole in a scene that he was so influential in bringing to life. It’s impossible to count how many people over the last 30+ years his presence touched directly through his performances, in addition to indirectly through his music and clothing. He was a visionary shaman who knew what was his to do and who did it with no regrets. While we mourn his departure, we can be grateful for what was provided and made possible in the hands of this shaman, and strive to live as he encouraged us through his music and work: to remember that ‘we are all connected in the great circle of life’ and that ‘we are star travellers.’ And as he and we ‘journey into the next world’ in our ‘waking dreams’, to ‘live what you love every moment of your life, right now’ – as he did. You’re going to laugh about it one of these days, so you might as well laugh now.

STAY CONNECTED